|

Saturday Evening Post

May 12, 1956

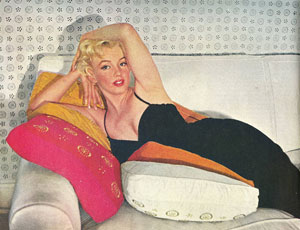

The New Marilyn Monroe - Part Two

By Pete Martin

PART THREE COMING

SOON!!!

“That nude calendar Marilyn Monroe posed

for will probably be reprinted as long as we have men with twenty-twenty

vision in this country,” Flack Jones told me. Jones had put in

several years as a publicity worker at Marilyn Monroe’s Hollywood studio

before opening his own public-relations office. “Curious thing

about it,” Jones went on, “when that calendar first came out, it had

no bigger sale than any other nude calendar.” “That nude calendar Marilyn Monroe posed

for will probably be reprinted as long as we have men with twenty-twenty

vision in this country,” Flack Jones told me. Jones had put in

several years as a publicity worker at Marilyn Monroe’s Hollywood studio

before opening his own public-relations office. “Curious thing

about it,” Jones went on, “when that calendar first came out, it had

no bigger sale than any other nude calendar.”

“You may not know it, but there’s a steady sale for such calendars.

You might think that there are too few places where you can hang

them up to make them worthwhile. But there’re lots of places where

they fit in very nicely – truckers’ havens, barbershops, bowling

alleys, poolrooms, washrooms, garages, toolshops, taprooms, taverns –

joints like that. The calendar people always publish a certain

number of nude calendars along with standards like changing autumn leaves,

Cape Cod fishermen bringing home their catch from a wintry sea, Old Baldy

covered with snow. You’re not in the calendar business unless you

have a selection of sexy calendars. The sale of the one for which

Marilyn posed was satisfactory, but not outstanding. It only became

a “hot number” when the public became familiar with it.”

Billy Wilder, the Hollywood director who directed Marilyn in The Seven

Year Itch, is witty, also pungent, pithy, and is not afraid to say what he

thinks. “When you come right down to it,” Wilder told me,

“that calendar is not repulsive. It’s quite lovely. Marilyn’s

name was already pretty big when the calendar story broke. If it

hadn’t been, nobody would have cared one way or the other. But

when it became known that she had posed for it, I think that, if anything,

it helped her popularity. It appealed to people who like to read

about millionaires who started life selling newspapers on the corner of

Forty-second and Fifth avenue; then worked their way up. It was as

if Marilyn had been working her way through college, for that pose took

hours. Here was a girl who needed dough, and she made it by honest

toil.”

“I was working on the Fox Western Avenue lot when this worried man from

Fox came tearing in wringing his hands,” Marilyn told me recently.

“He took me into my dressing room to talk about the horrible thing

I’d done in posing for such a photograph. I could think of nothing

else to say, so I said apologetically, ‘I thought the lighting the

photographer used would disguise me.’ I thought that worried man

would have a stroke when I told him that.

“What had happened was I was behind in my rent at the Hollywood

Studio Club, where girls stay who hope to crash the movies. You’re

only supposed to get one week behind in your rent at the club, but they

must have felt sorry for me because they’d given me three warnings.

A lot of photographers had asked me to pose in the nude, but I’d

always said, ‘No.’ I was getting five dollars an hour for plain

modeling, but the price for nude modeling was fifty for an hour. So

I called Tom Kelley, a photographer I knew, and said, ‘They’re kicking

me out of here. How soon can we do it?’ He said, ‘We can

do it tomorrow.’

“I didn’t even have to get dressed, so it didn’t take long. I

mean it takes longer to get dressed than it does to get undressed. I’d

asked Tom, ‘Please don’t have anyone else there except your wife,

Natalie.’ He said, ‘OK.’ He only made two poses. There

was a shot of me sitting up and a shot of me lying down. I think the

one of me lying down is the best.

“I’m saving a copy of that calendar for my grandchildren,” Marilyn

went on, all bright-eyed. “There’s a place in Los Angeles which

even reproduces it on bras and panties. But I’ve only autographed

a few copies of it, mostly for sick people. On one I wrote, ‘This

may not be my best angle,’ and on the other I wrote, ‘Do you like me

better with long hair?’”

I said to Marilyn that Roy Craft, who is one of the publicity men at Fox,

had told me that he had worked with her for five years, and that in all

that time he’d never heard her tell a lie. “That’s a mighty

fine record for any community,” I said.

“It may be a fine record,” she admitted, “but it has also gotten me

into trouble. Telling the truth, I mean. Then, when I get into

trouble by being too direct and I try to pull back, people think I’m

being coy. I’m supposed to have said that I dislike being

interviewed by women reporters, but that it’s different with gentlemen

of the press because we have a mutual appreciation of being male and

female. I didn’t say I disliked women reporters. As dumb as

I am, I wouldn’t be that dumb, although that in itself is kind of a

mysterious remark because people don’t really know how dumb I am. But

I really do prefer men reporters. They’re more stimulating.”

I asked Flack Jones in Hollywood, “When did this business of her making

those wonderful Monroe cracks start?”

“You mean when somebody asked her what she wears in bed and she said,

‘Chanel Number Five’?” Jones asked. “You will find some who

will tell you that her humor content seemed to pick up the moment she

signed a contract with the studio, and that anybody in the department who

had a smart crack lying around handy gave it to her. Actually, there

were those who thought that more than the department was behind it.

‘Once you launch such a campaign,’ they said, ‘it stays launched’.

It’s like anyone who has a smart crack to unleash attributing it

to a Georgie Jessel or to a Dorothy Parker or whoever is currently smart

and funny.’ There was even a theory that the public contributed

some of Marilyn’s cracks by writing or calling a columnist like Sidney

Skolsky or Herb Stein, and giving him a gag, and he’d attribute it to

Marilyn, and so on around town. But the majority of the thinking was

that our publicity department gave her her best cracks.”

“Like what?” I asked. “Like for instance. I’ll have to

lead up to it; as you know, in my business you can be destroyed by one bad

story – although that’s not as true as it used to be – and when the

story broke that Marilyn had posed in the nude for a calendar and the

studio decided that the best thing to do was to announce the facts

immediately instead of trying to pretend they didn’t exist, we said that

Marilyn was broke at the time and that she’d posed to pay her room rent,

which was true. Then, to give it the light touch, when she was

asked, ‘Didn’t you have anything on at all when you were posing for

that picture?’ we were supposed to have told her to say, ‘I had

the radio on.’”

Flack Jones paused for a long moment. “I’m sorry to disagree

with the majority,” he said firmly, “but she makes up those cracks

herself. Certainly that ‘Chanel Number Five’ was her own.”

When I told Marilyn about this, she smiled happily. “He’s right.

It was my own,” she said. “The other one – the calendar

crack – I made when I was up in Canada. A woman came up to me

asked, ‘You mean to say you didn’t have anything on when you had that

calendar picture taken?’ I drew myself up and told her, ‘I did,

too, have something on. I had the radio on.’”

“Giver her a minute to think and Marilyn is the greatest little old

ad-lib artist you ever saw,” Flack Jones had insisted. “She

blows it in sweet and it comes out that way. One news magazine

carried a whole column of her quotes I’d collected, and every one of

them was her own. There’ve been times when I could have made face

in this industry by claiming that I put some of those cracks into her

mouth, but I didn’t do it. This girl makes her own quotables.

She’ll duck a guy who wants to interview as long as she can, but

when she finally gets around to it, she concentrates on trying to give him

what he wants – something intriguing, amusing and off-beat. She’s

very bright at it.

“A writer was commissioned to write a story for her for a magazine,”

Jones said. “The subject was to be what Marilyn eats and how she

dresses. As I recall it, the title was to be How I Keep My Figure,

or maybe it was How I Keep in Shape. The writer talked to Marilyn;

then ghosted the article. He wrote it very much the way she’d told

it to him, but then had to pad it out a little because he hadn’t had too

much time with her. As a result, in one section of his article he

had her saying that she didn’t like to get out in the sun and pick up a

heavy tan because a heavy tan loused up her wardrobe by confusing the

colors of her dresses and switching around what they did for her.

“The article read good to me, and I took it over to Marilyn for her

corrections and approval. Most of the stuff was the routine thing

about diet, but when she came to the part about ‘I don’t like suntan

because it confuses the coloring of my wardrobe,’ she scratched it out.

I asked her, ‘What’s the matter?’

“’That’s ridiculous,’ she said. ‘Having a suntan doesn’t

have anything to do with my wardrobe.’ I said, ‘You’ve got to say

something, Marilyn. After all, the guy’s article is pretty short

as it is.’ She thought for a minute; then wrote, ‘I do not suntan

because I like to feel blonde all over.’ I saw her write that with her

own hot little pencil.

“The magazine which printed that story thought her addition so great

that they picked it out and made it a subtitle. She’d managed to

transpose an ordinary paragraph about wardrobe colors into a highly

exciting, beautiful, sexy mental image. Some guys have said to me,

‘Why, that dumb little broad couldn’t have thought that up. You

thought it up, Jones.’ I wish I could say, ‘Yeah, I did.’ But

I didn’t. Feeling blonde all over is a state of mind,” he said

musingly. “I should think it would be a wonderful state of mind if

you’re a girl.

“One reason why she’s such a good interview,” Flack Jones went on,

“is that she uses her head during such sessions. She tries to say

something that’s amusing and quotable, and she usually does. When

I worked with Marilyn I made it a practice to introduce her to a writer

and go away and leave her alone, on the grounds that a couple of grown

people don’t need a press agent tugging at their sleeves while they get

acquainted. So if her interviews have been any good, it’s her

doing.”

“One day she gave a tape interview and it was all strictly ad-lib,” he

said. “I know, because I had a hard time setting it up. It

was for a man who was doing one of those fifteen-minute radio interviews

here in Hollywood, to be broadcast afterward across the country. We

had a frantic time trying to get him the time with her, but finally he got

his recorder plugged in, and the first question he pitched her was a

curve. He wanted to know what she thought of the Stanislavsky school

of dramatic art or whatever. Believe it or not, old Marilyn unloaded

on him with a twelve-minute dissertation on Stanislavsky that rocked him

back on his heels.”

“Does she believe in the Stanislavsky method?” I asked.

“She agreed with Stanislavsky on certain points,” Jones said. “And

she disagreed on others, and she explained why. It was one of the

most enlightening discussions on the subject I’ve ever heard. It

came over the radio a couple of nights later, and everybody who listened

said, ‘Oh, yeah? Some press agent wrote that interview for her.’

My answer to that was, ‘What press agent knows that much about

Stanislavsky?’ I don’t.”

In the course of my research, before interviewing Marilyn, I’d

discovered that Billy Wilder agreed with Jones. “I think that she

thinks up those funny things for herself,” he said. Wilder’s

Austrian background gives his phrases an off-beat rhythm, but because of

its very differentness, his way of talking picks up flavor and extra

meaning.

“I think also that she says those funny things without realizing that

they’re so funny,” Wilder said. “One very funny thing she said

involves the fact that she has great difficulties in remembering her

lines. Tremendous difficulties. I’ve heard of one director

who wrote her lines on a blackboard and kept the blackboard just out of

camera range. The odd thing is that if she has a long scene for

which she has to remember a lot of words, she’s fine once she gets past

the second word. If she gets over that one little hump, there’s no

trouble. Then, too, if you start a scene and say ‘Action!’ and

hers is the first line, it takes her ten to fifteen seconds to gather

herself. Nothing happens during those fifteen seconds. It

seems a very long time.”

“How about an example of when she bogged down on a second word,” I

asked.

“For instance, if she had to say, ‘Good morning, Mr. Sherman,”

Wilder told me, “she couldn’t get out the word ‘morning.’ She’d

say, ‘Good….’ And stick. Once she got ‘morning’ out,

she’d be good for two pages of dialogue. It’s just that

sometimes she trips over mental stumbling blocks at the beginning of a

scene.

“Another director should be telling you this story, not me,” Wilder

said. “This other director was directing her in a scene in a

movie, and she couldn’t get the lines out. It was just muff, muff,

muff and take, take, take. Finally, after Take Thirty-two, he took

her to one side, patted her on the head, and said, ‘Don’t worry,

Marilyn, honey. It’ll be all right.’ She looked up into his face

with those big wide eyes of hers and asked, ‘Worry about what?’ She

seemed to have no idea that thirty-two takes is a lot of takes.”

When I sat down to talk to Marilyn, I said, “I’ve tried to trace those

famous remarks attributed to you and find out who originated them.”

“They are mine,” Marilyn told me. “Take that Chanel Number

Five one. Somebody was always asking me, ‘What do you sleep in,

Marilyn? Do you sleep in PJs? Do you sleep in a nightie? Do

you sleep raw, Marilyn?’ It’s one of those questions which make

you wonder how to answer them. Then I remembered that the truth is

the easiest way out, so I said, ‘I sleep in Chanel Number Five,’

because I do. Or you take the columnist, Earl Wilson, when he asked

me if I have a bedroom voice. I said, ‘I don’t talk in the

bedroom, Earl.’ Then, thinking back over that remark, I thought

maybe I ought to say something else to clarify it, so I added, ‘because

I live alone.’”

The phone rang in her apartment, and she took a call from one of the

handpicked few to whom she’d given her privately listed number. While

she talked I thought back upon a thing Flack Jones had said to me

thoughfully, “I’m no psychiatrist or psychologist, but I think that

Marilyn has a tremendous inferiority complex. I think she’s scared

to death all the time. I know she needs and requires somebody to

tell her she’s doing well. And she’s extremely grateful for a

pat on the back.”

“Name me a patter,” I said.

“For example,” he said, ‘when we put her under contract for the

second time, her best friend and encourager was the agent, Johnny Hyde,

who was then with the William Morris Agency, although he subsequently died

of a heart attack. Johnny was a little guy, but he was Marilyn’s

good friend, and, in spite of his lack of size, I think that she had a

father fixation on him.

“I don’t want to get involved in the psychology of all this,” Flack

Jones continued, “because it was a very complicated problem, of which I

have only a layman’s view, but I honestly think that Marilyn’s the

most complicated woman I’ve ever known. Her complexes are so

complex that she has complexes about complexes. That, I think, is

one reason why she’s always leaning on weird little people who attach

themselves to her like remoras, and why she lets herself be guided by

them. A remora is a sucker fish which attaches itself to a bigger

fish and eats the dribblings which fall from the bigger fish’s mouth.

After she became prominent, a lot of these little people latched

onto Marilyn. They told her that Hollywood was a great, greedy ogre

who was exploiting her and holding back her artistic progress.”

I said that the way I’d heard it, those hangers-on seemed to come and

go, and that her trail was strewn with those from whom she had detached

herself. I’d been told that the routine was for her to go down one

day to the corner for the mail or a bottle of milk and not come back;

not even wave good-bye.

“But she has complete confidence in these little odd balls, both men and

women, who latch onto her, while they’re latched,” Jones said. “I’m

sure their basic appeal to her has always been in telling her that

somebody is taking advantage of her, and in some cases they’ve been

right. This has nothing to do with your story, but it does have

something to do with my observation that she’s frightened and insecure,

and she’ll listen to anybody who can get her ear.”

“Johnny Hyde was no remora,” I said. “Johnny was a switch on

the usual pattern,” Jones agreed. “He was devoted to her. He

could and did do things for her. I happened to know that Johnny

wanted to marry her and Marilyn wouldn’t do it. She told me, ‘I

liked him very much, but I don’t love him enough to marry him.’ A

lot of girls would have married him, for Johnny was no only attractive, he

was wealthy, and when he died Marilyn would have inherited scads of money,

but while you may not believe it, she’s never cared about money as

money. It’s only a symbol to her.

“A symbol of what?” I asked.

“It’s my guess that to her it’s a symbol of success. By the

same token I think that people have talked so much to her about not

getting what she ought to get that a lack of large quantities of it has

also become a symbol of oppression in her mind. If I sound

contradictory, that’s the way it is.”

When Marilyn had completed her phone call, I put it up to her, “I guess

you’ve heard it argued back and forth as to whether you are a

complicated person or a very simple person, even a naïve person,” I

said. “Which do you think it right?”

“I think I’m a mixture of simplicity and complexes,” she told me.

“But I’m beginning to understand myself now. I can face

myself more, you might say. I’ve spent most of my life running

away from myself.”

It didn’t sound very clear to me, but I pursued the subject further.

“For example,” I asked, “do you have an inferiority complex?

Are you beset by fears? Do you need someone to tell you that

you’re doing well all the time?”

“I don’t feel as hopeless as I did,” she said. “I don’t know why

it is. I’ve read a little of Freud and it might have to do with

what he said. I think he was on the right track.” I gave up.

I never found out what portions of Freud she referred to or what

“right track” he was on.

“What happened in 1952, when the studio sent you to Atlantic City to be

grand marshal of the annual beauty pageant?” I asked Marilyn instead.

“Did you mind going?”

She smiled. “It was all right with me,” she said. “At

the time I wanted to come to New York anyhow. There was somebody I

wanted to see here. This is why it was hard for me to be on time

leaving New York for Atlantic City for that date. I missed the train

and the studio chartered a plane for me, but it didn’t set the studio

back as much as they let on. The could afford it.”

Flack Jones had told me that story too. “They’d arranged a big

reception for Marilyn at Atlantic City,” he said. “There was a

band to meet her at the train, and they mayor was to be on hand. Marilyn

and the flacks who were running interference for her were to arrive on a

Pennsylvania Railroad train at a certain hour, but, as usual, Marilyn was

late, and when they got to the Pennsylvania Station the train had pulled

out. So there they were, in New York, with a band and the mayor

waiting in Atlantic City. Charlie Einfeld, a Fox vice-president –

and Charlie can operate mighty fast when he has to – got on the phone

and chartered an air liner – the only one available for charter was a

forty-six-seat job; it was an Eastern Air Lines plane as I recall it –

and they all went screaming across town in a limousine headed for Idlewind.

“The studio’s magazine man in New York, Marilyn and a flack from out

there on the Coast boarded the plane and took off for Atlantic City,”

Flack Jones said. “Bob and the Coast flack were so embarrassed at

missing the train, and the plane was such a costly substitute that they

were sweating like pigs. On this big air liner there was a steward

aboard – they’d shanghaied a steward in a hurry from some place to

serve coffee – but all of this didn’t bother Marilyn at all. She

tucked herself into a seat back in the tail section, hummed softly; then

fell fast asleep and slept the whole way. The other two sat up front

with the steward, drinking quarts of coffee because that was what he was

being paid to serve. They drank an awful lot of coffee.”

Flack Jones said that Marilyn and her outriders were met at the Atlantic

City airport by a sheriff’s car and that they were only three minutes

late for the reception for Marilyn on the boardwalk. There she was

given an enormous bouquet of flowers, and she perched on the folded-down

top of a convertible, to roll down the boardwalk with a pres of people

following her car.

“She sat up there like Lindbergh riding down Broadway on his return from

Paris,” Flack Jones said. “The people and the cops and the

beauty-carnival press agents followed behind like slaves tied to her

chariot wheels. That is, she managed to move a little every once in

a while when the crowd could be persuaded to back away. Then Marilyn

would pitch a rose at the crowd and it would set them off again, and

there’d be another riot. This sort of thing went on – with

variations – for several days. It was frantic.

“But,” Flack Jones explained, “there was one publicity thing which

broke which wasn’t intended to break. It was typical of the way

things happen to Marilyn without anybody devising them. When each

potential Miss America from a different part of the country lined up to

register, a photograph of Marilyn greeting her was taken. Those

pictures were serviced back to the local papers and eventually a shot of

Miss Colorado with Marilyn wound up in a Denver paper; and a shot of Miss

California and Marilyn in the Los Angeles and San Francisco papers, and so

forth.”

For a moment Flack Jones collected his thoughts in orderly array; then

went on, “Pretty soon in came an Army public information officer with

four young ladies from the Pentagon. There was a WAF and a WAC and a

lady Marine and a WAVE. The thought was that it would be nice to get

a shot of Marilyn with ‘the four real Miss Americas’ who were serving

their country, so they were lined up. IT was to be just another of

the routine, catalogue shots we’d taken all day long, but Marilyn was

wearing a low-cut dress which showed a bit of cleavage. That would

have been all right, since the dress was designed for eye level, but one

of the photographers climbed up on a chair to shoot the picture.”

The way Marilyn described this scene to me was this: “I had met the

girls from each state and had shaken hands with them,” she said. “Then

this Army man got the idea of aiming his camera down my neck while I posed

with the service girls. It wasn’t my idea for the photographer to

get up on a chair.”

“Nobody thought anything of it at the time,” Jones had told me, “and

those around Marilyn went on with the business of their workday world.

In due course the United Press – among others – serviced that

shot. Actually it was a pretty dull picture because, to the casual

glance, it just showed five gals line up looking at the camera.”

Jones said that when the shot of the four service women and Marilyn went

out across the country by wirephoto, editors took one look at it and

dropped it into the nearest wastebasket because they had had much better

art from Atlantic City.

“That night the Army PIO officer drifted back to the improvised press

headquarters set up for the Miss America contest,” Flack Jones said.

“He took one look and sent out a wire ordering that the picture be

stopped.”

“On what grounds?” I asked.

“On grounds that that photograph showed too much meat and potatoes, and

before he’d left the Pentagon he’d been told not to have any

cheesecake shots taken in connection with the girls in his charge. Obviously

what was meant by those instructions was that he shouldn’t have those

service girls sitting on the boardwalk railings showing their legs or

assuming other undignified poses. There was nothing in that PIO

officer’s instructions which gave him the right to censor Marilyn’s

garb, but he ordered that picture killed anyhow.”

“On grounds that that photograph showed too much meat and potatoes, and

before he’d left the Pentagon he’d been told not to have any

cheesecake shots taken in connection with the girls in his charge. Obviously

what was meant by those instructions was that he shouldn’t have those

service girls sitting on the boardwalk railings showing their legs or

assuming other undignified poses. There was nothing in that PIO

officer’s instructions which gave him the right to censor Marilyn’s

garb, but he ordered that picture killed anyhow.”

According to Jones, every editor who had junked that picture immediately

reached down into his wastebasket, drew it out and gave it a big play.

“In Los Angles it ran seven columns,” he said, “and it got a

featured position in the Herald Express and the New York Daily News.

All the way across country it became a celebrated picture, and all

because the Army had ‘killed’ it.”

He was silent for a moment; then he said, “Those who were with her told

me afterward that it had been a murderous day, as any days is when

you’re with Marilyn on a junket,” he went on. “The demands on

her and on those with her are simply unbelievable. But finally she

hit the sack about midnight because she had to get up the next day for

other activities. The rest of her crowd had turned in too, when they

got a call from the U.P. in New York, asking them for a statement from

Marilyn about ‘that picture.’”

“’What picture?’ our publicist-guardian asked, and it was then that

they got the story. They hated to do it, but they rousted Marilyn

out of bed. She thought it over for a while; then issued a statement

apologizing for any possible reflection on the service girls, and making

it plain that she hadn’t meant it that way. She ended with a

genuine Monroeism. ‘I wasn’t aware of any objectionable décolletage

on my part. I’d noticed people looking at me all day, but I

thought they were looking at me all day, but I thought they were looking

at my grand marshal’s badge.’ This was widely quoted, and it had

the effect of giving the whole thing a lighter touch. The point is

this: a lot of things happen when Marilyn is around.” He shook his

head. “Yes, sir,” he said. “A lot of things.

“Another example of the impact she packs: when she went back to New York

on the Seven Year Itch location,” Jones went on. “All of a

sudden New York was a whistle stop, with the folks all down to see the

daily train come in. When Marilyn reached LaGuardia, everything

stopped out there. One columnist said that the Russians could have

buzzed the field at five hundred feet and nobody would have looked up.

There has seldom been such a heavy concentration of newsreel

cameramen anywhere. From then on in, during the ten days of her

stay, one excitement followed another. She was on the front page of

the Herald Tribune, with art, five days running, which I’m told set some

sort of a local record.

“In the case of The Itch, there was a contractual restriction

situation,” Flack Jones said. “The studio’s contract called

for the picture’s release to be held up until after the Broadway run of

the play. When Marilyn went back to New York for the location shots

for itch, the play version was still doing a fair business, but it was

approaching the end of its long run. If you bought a seat, the house

was only half full. Then Marilyn arrived in New York and shot off

publicity sparks and suddenly The Itch had S.R.O. signs out again. The

result was that it seemed it was never going to stop its stage run; so,

after finishing the picture, Fox had to pay out an additional hundred and

seventy-five thousand dollars to the owners of the stage property for the

privilege of releasing their movie.

“Things reached a new high – and no joke intended,” Flack Jones went

on, “when Billy Wilder shot the scene where her skirts were swept up

around her shoulders by a draft from a subway ventilator grating. That

really set the publicity afire again, and shortly after that The Itch

location company blew town while they were ahead. The unit

production manager had picked the Trans-Lux Theater on Lexington Avenue

for the skirt-blowing scene. He’d been down there at two o’clock

in the morning to case the spot; he’d reported happily, ‘The street

was fully deserted,’ and he’d made a deal with the Trans-Lux people

for getting the scene shot there because there was nobody on the street at

that hour.

“It seemed certain that Billy Wilder would have all the room in the

world to work, and he had left word that nobody was to know what location

he’d selected, because he didn’t want crowds. But word leaked

out. It was on radio and TV and in the papers, so instead of secrecy

you might almost say that the public was being urged to be at Lexington

Avenue on a given night to watch Marilyn’s skirts blow. Instead of

having a nice, quiet side street in which to work, Wilder had all the

people you can pack on a street. Finally the cops roped off the

sidewalk on the opposite side to restrain the public, and they erected a

barricade close to the movie camera. But that wasn’t good enough,

and they had to call out a whole bunch of special cops.”

Flack Jones said that when Wilder was ready to shoot, there were 200 or

300 photographers, professional and amateur, swarming over the place.

Then Marilyn made her entrance from inside the theater out onto the

sidewalk, and when she appeared the hordes really got out of control and

there was chaos. Finally Wilder announced that he’d enter into a

gentleman’s agreement. If the press would retire behind the

barricades, and if the real working photographers would help control the

amateurs, he would shoot the scene of Marilyn and Tom Ewell standing over

the subway grating; then he’d move the movie camera back and the amateur

shutter hounds could pop away at Marilyn until they were satisfied.

“So the New York press took care of the amateurs and made them quit

popping their flashbulbs,” Flack Jones said. “Wilder got the

scene and the volunteer snapshooters got their pictures. Everybody

was there. Winchell came over with DiMaggio, who showed a proper

husbandly disapproval of he proceeding. I myself couldn’t see why

Joe had any right to disapprove. After all, when married the girl

her figure was already highly publicized, and it seemed odd if he had

suddenly decided hat she should be seen only in Mother Hubbards.”

I asked Marilyn herself if she thought that Joe had disapproved of her

skirts blowing around her shoulders in that scene. I said I had

heard his reaction described in two ways: that he had been furious

and that he had taken it calmly.

“One of those two is correct,” Marilyn said. “Maybe you can

figure it out for yourself if you’ll give it a little thought.” Something

told me that, in her opinion, Joe had been very annoyed indeed. And

while we were on the subject of Joe, it seemed a good time to find out

about how things had been between them when they had been married, and the

unbelievable scene which accompanied the breaking up of that marriage.

“Not in his wildest dreams could a press agent imagine a series of

event like that,” Flack Jones had told me.

When I brought the subject up, Marilyn said, “For a man and a wife to

live intimately together is not an easy thing at best. It it’s not

just exactly right in every way it’s practically impossible, but I’m

still optimistic.” She sat there being optimistic. Then she

said, with feeling, “However, I think TV sets should be taken out of the

bedroom.”

“Did you and Joe have one in your bedroom?” I asked.

“No comment,” she said emphatically.

“But everything I say to you I speak from experience. You can make

what you want of that.”

She was quiet for a moment; then she said, “When I showed up in divorce

court to get my divorce from Joe, there were mobs of people there asking

me bunches of questions. And they asked, ‘Are you and Joe still

friends?’ and I said, ‘Yes, but I still don’t know anything about

baseball.’ And they all laughed. I don’t see what was so

funny. I’d heard that he was a fine baseball player, but I’d

never seen him play.”

“As I said, the final scenes of All American Boy loses Snow White were

unbelievable,” Flack Jones told me. “Joe and Marilyn rented a

house on Palm Drive, in Beverley Hills, and we had a unique situation

there with the embattled ex-lovebirds both cooped in the same cage. Marilyn

was living on the second floor and Joe was camping on the first floor.

When Joe walked out of that first floor, it was like the

heart-tearing business of a pitcher taking the long walk from the mound to

the dugout after being jerked from the fame in a World Series.”

|