|

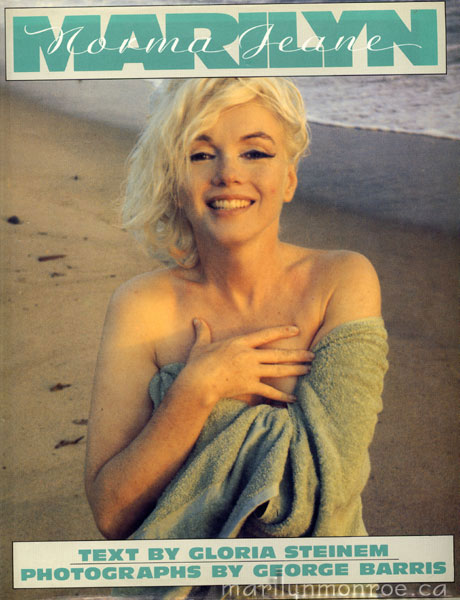

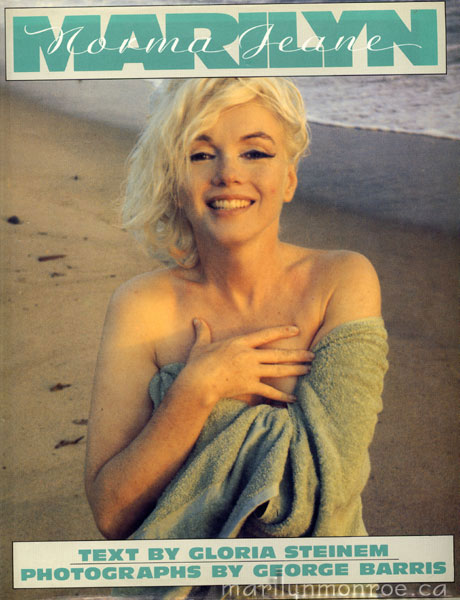

This was the very first Marilyn book that I ever owned. So it has a special place in my heart. The text is an interesting read and the Barris photos are gorgeous. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

BOOK REVIEW BY DAVID MARSHALL I am getting very near the end of my

Marilyn books so when it comes to Steinemís ìMarilynî, think of it as a

case of saving the best for lastÖ Now that Iíve written that line,

I realize I have to back it up-- or at least explain why this book has become

one of my favorites. There are certainly better photo books, (Mailerís

ìMarilynî comes to mind), more in-depth biographical facts found elsewhere,

(like Leaming and Spoto), and certainly a lot more to her death than is

mentioned here, (ìGoddessî and ìLast Takeî are both flawed but they are

also both energetic and filled with small facts and clues to give you an idea of

at least Marilynís frame of mind and the company she kept during that last

summer). And while Fred Lawrence Guiles provided the most heartfelt rendition of

the Monroe story, Gloria Steinem brings a new bent to the story without ever

being relentless about it. And although it may be an accepted thought now nearly

20 years after Steinemís work was published, looking at Marilyn Monroe from a

feminist perspective was something unheard of at the time. Prior to Steinem, the

popular thought was that most women held a sort of resentment towards Monroe,

considered her more of a joke than an actress, let alone a trailblazer in

womanís fight for equality. We, (or at least the majority of

the public prior to the 1980s), tend to forget what a powerful figure Marilyn

was. Sure Bette Davis and others had fought against their studios and helped

actors break out of the studio restraints, but when Marilyn risked everything to

follow her own path by deserting Hollywood and heading off to New York, she

proved that a woman could be a powerful figure to reckon with. As we all know,

there was a hell of a lot more to her than the wiggle-giggle gal who had such a

provocative walk, but it took someone of Steinemís stature to point the fact

out to Middle America. If the online groups had been around in the 80s, maybe it

wouldnít have been such a surprise that the majority of her fans were women,

that it took a feminine perspective to see beyond the moistened and parted lips,

the bleached hair and perfect proportions. And that is what Steinem brings to

the table. Like most authors covering the Monroe story in the 80s, she too

sources a lot of her research to Robert Slatzer. And sure thereís a lot of the

Kennedy finger pointing. But beyond that, Steinem brings a near lyrical sense of

Marilyn to these pages, aided greatly by illustrating the majority of the book

with the wonderful George Barris sessions from the summer of ë62. Could be

thatís one of the reasons I enjoyed the book so much-- the pictures. But

beyond that, by using so many of the Barris photos, the Marilyn most often

overlooked-- the Marilyn of 1962-- is present throughout the entire work. By

giving only a fleeting glimpse of the flying skirt of ìSeven Year Itchî,

Steinem instead presents us with words and photos that accentuate the fact that

this is our near-to-last look at a remarkable woman. Of all the photographers

she worked with, perhaps Barris is the one we should rely on the most to show us

just what was lost. The photos show a woman that we now know would be living

only a little over a month after these images were first snapped. And as such,

the entire concept of Marilyn Monroe becomes timeless. Looking at the photos one

forgets that this was over forty years ago-- the images of her on the beach as

well as those taken in the hills, could be yesterday. By illustrating her words

with Barris, Steinem brings Marilyn even closer to us as we realize how timeless

she truly was. Another reason why I love this

book so much. Steinem is a great writer. The talent she has shown in her essays

for Ms. Magazine, the periodic pieces that appear in the New Yorker, or in the

several collections of her magazine work, is here even more evident. The book

has the feeling that Steinem has

allowed herself the sheer space to fully explore her own feelings rather than

restrict herself to a single column. Just one example, a particular favorite

from the book-- ìIn the 1930s, when English

critic Cyril Connolly proposed a definition of posterity to measure whether a

writerís work had stood the test of time, he suggested that posterity should

be limited to ten years. The form and content of popular culture were changing

too fast, he explained, to make any artist accountable for more than a decade. ìSince then , the pace of change

had been accelerated even more. Everything from the communications revolution to

multinational entertainment has altered the form of culture. Its content has

been transformed by civil rights, feminism, an end to film censorship, and much

more. Nonetheless, Monroeís personal and intimate ability to inhabit our

fantasies has gone right on. As I write this, she is still better known than

most living movie stars, most world leaders, and most television personalities.

The surprise is that she rarely has been taken seriously enough to ask why that

is so.î For most readers of Steinemís work on Monroe, that situation is changing. More and more people are wondering just what was it about this woman, an icon of the long ago 1950s, a woman most can not recall as a living person, that still has such power over us. Thanks to Steinem and others, we are now taking Marilyn seriously enough to ask why. |

|||||||||||||||||||